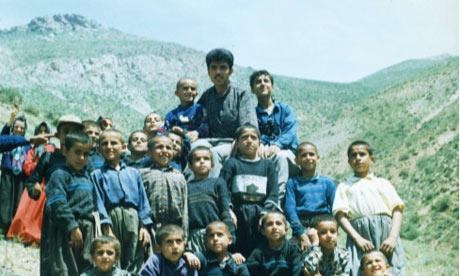

Farzad Kamangar was a Kurdish schoolteacher and civic activist hanged for the crime of moharebeh (“warring against God”) alongside several other political prisoners at Evin Prison near Tehran on the morning of May 9, 2010. Kamangar’s execution was condemned by the European Union and cited in a UNESCO report on the pressures facing Iran’s educational system. Kamangar had been imprisoned for four years before his execution. Some believe that Iranians hanged him because he used to take students and teach them Kurdish outside school hours. The state charged him to have connection with Kurdish parties outside country which he always denied. Teaching a language other than Farsi is forbidden in Iran.

A few months before his death sentence was carried out, Farzad Kamangar described his emotional state and his hopes for Kurdistan in this letter to his beloved. As he wrote: “Believe me when I say that, for me, our country is just one part of this world. We have no intention of building a wall around it, and we don’t intend to isolate it from the rest of the world, but the grievances and the pain suffered by its people make it their belonging to this land all the sweeter.”

An Unpublished Letter by Farzad Kamangar

Hello again, my darling!

When you asked me what I would like you to play for me, I got stuck for a moment. I went silent, turned everything upside down in my mind in order to find a song which could best express my feelings after so many months spent away from you.

I wanted to pick the most beautiful and romantic song ever written. Before I even spoke a word, you played that sweet song “Maryam” for me, with all its beauty, so that the phone lines brought all of your feeling and passion into my heart alongside that song.

The question you asked and the song you played gave me an excuse to write this heartfelt letter. I know it will be opened and closed many times, but I hope that it will, eventually, reach your hands and that you will be its final reader.

My sweetheart, every song that I thought of had something to do with the gallows, a last kiss, cruel oppression, the arm of injustice, being hunted by tyranny, or a mother’s tears.

I feared that your fingers, when they touched so many words overflowing with pain, might stop playing, so I started searching among the songs of my motherland. I realized that our music had traces of blood, the smell of lead, and the marks of bootprints too. Once again, I feared that your eyes might fill with tears and that your hands would refuse to let your fingers play.

I decided to ask you to write your own song, either with lyrics or an instrumental, something filled to the brim with hope. Not a stolen song; a song we wouldn’t have to murmur to ourselves, one that wouldn’t put us behind bars, a song that doesn’t fill our eyes with tears when we sing it or glue our eyes to the picture hanging on the wall, one that doesn’t make us cry and sob. A song that we could sing around the Nowrooz [New Year’s] fire as loud as we can, hand in hand, dancing to it, laughing with it, singing it.

Just don’t forget: write the notes for a little girl who likes to call her mother “dâyeh” and women “jen”[1]. What a shame… she doesn’t know that tomorrow, when she becomes a mother herself, they will search her womb in hopes that the child belongs to the “first gender.” A little girl in a country where women, to secure their most basic rights, have to go to prison.

Write for that little girl who, when stepping into her adulthood, will have to go from jail to jail in search of her lost love, hastily looking up lists of names posted at the entrance, searching for the one which belongs to her beloved.

Write the notes of your song for a little boy who likes to say “tchûrak” for bread and “sû” for water[2]. What a shame… he doesn’t know that there is no word and no language which can bring prosperity to his working father’s bare table.

Write your notes for his father’s callused hands, for his mother’s diminishing eyesight. Write a song that will bring good news of bread, not one that will remind him of the poverty and the long years of injustice marking his life.

Write a poem for the mother who has long been waiting, her eyes riveted to the door, for her son to return. A mother who, every Thursday, away from others’ scrutinizing eyes, embraces the unknown tomb of her loved one, a mother who has put the sun to shame with all the patience and loyalty she has shown.

Write it for a father for whom the sight of every lonely cedar is a reminder of the solitude and alienation of the cemetery which has long held his child, a cemetery which he sees from afar and where he secretly yearns for the opportunity to break down in tears, for once, on the tomb of his own son.

Write a poem for a sister whose hope to see her brother’s wedding day still weighs on her, a sister whose eyes become clouded with tears when the singing and the celebrating from other people’s wedding ceremonies resonate in her every Friday, making her look up to the wall to stare at the dust-covered picture of her brother while her eyes grow misty.

My sweet darling! With me or without me, go back to our homeland. Don’t blame me for loving it without end. Believe me when I say that, for me, our country is just one part of this world. We have no intention of building a wall around it, and we don’t intend to isolate it from the rest of the world, but the grievances and the pain suffered by its people make it their belonging to this land all the sweeter. This pain has become part of our arteries and roots over the years; it is born alongside the inhabitants of our land.

Let your song be made there. Let the bitter taste of poverty be its rhythm and the hope for an equal world its beat.

There, in the midst of the mountains and oak forests that have been our people’s only friend and supporter, on the banks of rivers carrying the unshed tears of our people from the depths of the mountains out to remote seas, sit down and write your song.

There, with or without me, in the midst of all that beauty and glory which is the link of our attachment to this country, in the heart of a land forever pregnant with pain and whose children grow up only to suffer; sit down there, touch the earth in my stead, and write your song, a song which you will murmur in its ears:

O maternal land,

O motherland,

Here, buried in your heart,

Rest the bones and the memories of my ancestors.

Here are entombed my forefathers, my descendants and my children.

O my country,

You, the mother of my forerunners,

I wish I could caress your beauty once again,

Bear witness to your charm,

Company to your silence,

Remedy to your pains,

I wish I could shed your tears.

I wish I could…

I hope to see you and the sunrise again.

Farzad, Evin Prison, Section 7.

[1] Dâyeh and Jen are Kurdish for mother and woman.

[2] Kurdish equivalents for bread and water.

- حکومت نباید کارخانه قانون باشد - 03/04/2026

- کرمانشاه به عنوان پایتخت دولت انتقالی - 03/03/2026

- راگەیەندراوی ژمارە ١ - 03/02/2026